A basic question that comes up often at meetings of arts entrepreneurship educators is “what should we be teaching?” As I was preparing to write the editor’s introduction to the Winter 2016 issue of Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts, I realized that two articles in the issue as well as two additional articles we had recently published all contained studies of just that question: “What are the crucial skills for arts entrepreneurs?” Through both qualitative and quantitative inquiry, the four articles described several overlapping families of skills that I summarized in a table:

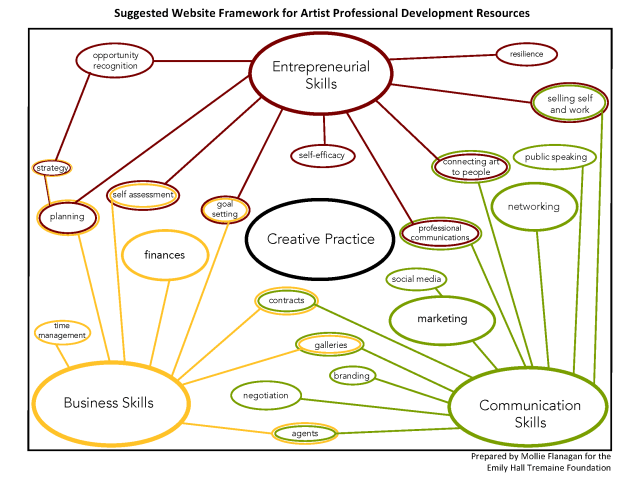

The skills families include networking, especially networking for collaboration (which is confirmed by some other research we’ve done recently); hard skills for business, although this is only considered crucial by 2 of the 4 research teams; two modes of cognition: the strategic and the creative; confidence or “self-efficacy” (which I’ve noted earlier is best taught or developed experientially); communication, including marketing communication; and understanding context and recognize opportunity, a core competency for entrepreneurs in any field.

With this summary, the core competencies for arts entrepreneurship begin to emerge, signaling the beginnings of the maturation of the field itself.

(Table source: Essig, L. (2016). Editor’s introduction to the Winter 2016 issue. Artivate: A Journal of Entrepreneurship in the Arts 5 (1), 1-3.)

sense, but in the research agenda sense. I basically completed my

sense, but in the research agenda sense. I basically completed my

The SEA audience is undergraduate arts students, primarily from Midwest colleges and universities. All of the programming, with the exception of two or three sessions designed for faculty, is geared toward introducing these young artists and designers to core self-employment business principles: how to communicate with clients; how to craft a financial plan; business models for artists. This last was delivered by two of my

The SEA audience is undergraduate arts students, primarily from Midwest colleges and universities. All of the programming, with the exception of two or three sessions designed for faculty, is geared toward introducing these young artists and designers to core self-employment business principles: how to communicate with clients; how to craft a financial plan; business models for artists. This last was delivered by two of my

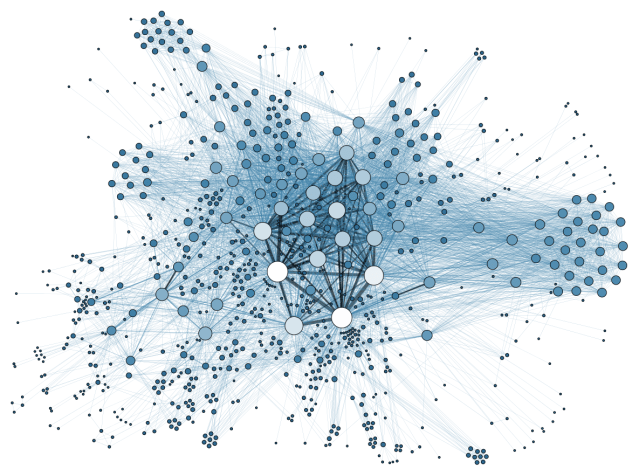

…the findings of several studies indicate that the broader entrepreneurs’ social networks (the more people they know and with whom they have relationships), the more opportunities they identify. This finding, too, is consistent with a pattern recognition perspective. Social networks are an important source of information for entrepreneurs, information that may contribute to the richness of their store of knowledge and the development of their cognitive frameworks. Further, social networks may be especially helpful to entrepreneurs in terms of honing or refining these frameworks (prototypes, exemplars). For instance, by discussing opportunities they have recognized with family, friends, and others, entrepreneurs may form more accurate and useful prototypes for identifying opportunities— cognitive frameworks helpful in determining whether ideas for new products or services are practical and potentially valuable rather than merely interesting or novel. (p. 113)

…the findings of several studies indicate that the broader entrepreneurs’ social networks (the more people they know and with whom they have relationships), the more opportunities they identify. This finding, too, is consistent with a pattern recognition perspective. Social networks are an important source of information for entrepreneurs, information that may contribute to the richness of their store of knowledge and the development of their cognitive frameworks. Further, social networks may be especially helpful to entrepreneurs in terms of honing or refining these frameworks (prototypes, exemplars). For instance, by discussing opportunities they have recognized with family, friends, and others, entrepreneurs may form more accurate and useful prototypes for identifying opportunities— cognitive frameworks helpful in determining whether ideas for new products or services are practical and potentially valuable rather than merely interesting or novel. (p. 113) For the first interactive exercise of the day, I allowed the existing nodes to remain physically in place (that is, the members sat together), but as the weekend progressed, I incentivized interaction across nodes and between people of dissimilar knowledges. In doing so, each individual added information into their newly forming network, helping its other members to develop the cognitive frameworks that support opportunity recognition. By the last exercise of day 2, participants wanted to hear more from each other than from me about the possibilities afforded by their new knowledges – a marker of success in building the ties that will support their individual arts entrepreneurial success moving forward.

For the first interactive exercise of the day, I allowed the existing nodes to remain physically in place (that is, the members sat together), but as the weekend progressed, I incentivized interaction across nodes and between people of dissimilar knowledges. In doing so, each individual added information into their newly forming network, helping its other members to develop the cognitive frameworks that support opportunity recognition. By the last exercise of day 2, participants wanted to hear more from each other than from me about the possibilities afforded by their new knowledges – a marker of success in building the ties that will support their individual arts entrepreneurial success moving forward.

As we begin to talk about the way artistic production and arts firms engage in the larger social system we call “the economy,” I wanted students to consider what might motivate an audience member to engage with their artistic work. Do they need it? Or do they want it? Does the audience for live music, for example, “consume” a concert hedonistically or for its use value? Rather than lecture on the topic drawing from the likes of Hirschman and Holbrook (it’s a small seminar class, after all) I wanted to engage them more viscerally and kinesthetically in these questions. So…I passed around a roll of toilet paper and said “Take what you need for the day.” There was an uncomfortable moment and a slight giggle, so I started things off, pulling enough TP off the roll to last a day. We ended up with piles of product in front of us of sizes that varied noticeably by gender. Then I pulled out a large

As we begin to talk about the way artistic production and arts firms engage in the larger social system we call “the economy,” I wanted students to consider what might motivate an audience member to engage with their artistic work. Do they need it? Or do they want it? Does the audience for live music, for example, “consume” a concert hedonistically or for its use value? Rather than lecture on the topic drawing from the likes of Hirschman and Holbrook (it’s a small seminar class, after all) I wanted to engage them more viscerally and kinesthetically in these questions. So…I passed around a roll of toilet paper and said “Take what you need for the day.” There was an uncomfortable moment and a slight giggle, so I started things off, pulling enough TP off the roll to last a day. We ended up with piles of product in front of us of sizes that varied noticeably by gender. Then I pulled out a large  bag of M&Ms and passed it around with the same direction, “Take what you need for the day.” Nods and smiles ensued – they got it. Some students took none of the candy, a couple of people (including me) took three dear little chocolate bits saying it would be just enough to satisfy their chocolate addiction for the day. From here we were able to talk about audience, about hedonic and use value, about pricing and, when I asked them to throw away half of their toilet paper, how scarcity might affect value and pricing.

bag of M&Ms and passed it around with the same direction, “Take what you need for the day.” Nods and smiles ensued – they got it. Some students took none of the candy, a couple of people (including me) took three dear little chocolate bits saying it would be just enough to satisfy their chocolate addiction for the day. From here we were able to talk about audience, about hedonic and use value, about pricing and, when I asked them to throw away half of their toilet paper, how scarcity might affect value and pricing.